by Mark E. Lasbury for Indiana On Tap

by Mark E. Lasbury for Indiana On Tap

The process for making beer is basically the same for all styles. A brewer will mash-in and mash-out the grain to produce a sugary liquid (sweet wort) as part of the brewing process. That wort is then boiled with hops, producing a sterile brew with the desired chemistry. The released sugars are fermented by yeast to alcohols and carbon dioxide and the beer is then clarified and matured. Fermentations may be a bit different for sours, and lagers might be clarified longer, but most of the processes are generally static. But don’t get me wrong, there are tricks of the trade. Every brewery has some twist that makes their beer uniquely theirs, even if you may not taste it or notice it on first glance.

The more one learns, the more he/she appreciates how far your brewers are going to produce a wonderful product for the patron, and those tweaks to the system can come at just about any step of the brewing process. Take for instance the milking of malted barley for its carbohydrates and then discarding the rest of the grain (typically called lautering or the mash-out) – there is one brewery in Indiana that does this in manner different than all others in the state. It may not be the only reason why Tin Man’s beer is so good, but knowing about it changes the experience of drinking their beer.

For Tin Man, it is the step in which sugars are collected for boiling that they have gone against the grain. Malted (germinated) barley may be one of the main ingredients of beer, but that doesn’t mean that all the barley makes it into the final product. The brewer is really just using barley for its sugars – like how that girl in high school used you for money because you had a good summer job with Chemlawn and were desperate enough to think that buying her that purebred Chow puppy she always wanted and all those clothes from Forever 21 would make her love you forever…… OK, maybe I’m getting off script.

To start making beer, you have to release the starches and enzymes (the enzymes break down the starches to fermentable sugars) in the barley grain so the sugars will be loose, not locked up inside cells where the yeast can’t get at them during fermentation. After the grain is milled to smaller pieces – and there is an art and science to this too – it is ready to be mixed with water to release the sugars into the water. This is the “mash in,” where the crushed barley (and other grains if they are being used) is/are stirred with water. There are hundreds of secret recipes for mashing in; different temperatures, different time periods, resting periods in between temperature cycles, the variants are innumerable, but in general, the hot water helps the released enzymes break down the remaining cells and the long chains of starch that are released from the burst cells.

After the mash in, the brewer has to get rid of the solids left over from the barley grain. As opposed to the mash in, this is called the “mash out” and can occur at different temp.s and time as well. Rinsing and re-rinsing the grain helps to get all the sugars out – called lautering, and is sometimes done in separate container from the original mash in. Logically enough, this occurs in a “lauter tun.” The sweet wort (the sugars and many other water soluble proteins and biochemical) gets separated from the mash through a false bottom in the lauter tun.

The barley husks are important here, because they act as a filter bed that holds up the grain while letting the sweet wort pass through. This is why the milling is important. It can’t be too fine because the husks will be too small to act as a filter bed. Once the initial wort is drained off the mash, it might be recirculated to get more of the sugars off of the grain. Then the grain itself is often raked around while sprinkling water on it (sparge water) to get that last fraction of the sugars. By the end of all this, a brewer has a sugar rich solution that is ready to be boiled. We’ve talked previously about why beer is boiled during, so click here for a refresher.

It’s in the separation of wort from grain where Tin Man Brewing in Evansville (and now Kokomo) has chosen to walk a different path. Instead of a lauter tun and sparging, they use a weird looking piece of equipment called a mash filter. Nick Davidson, one of the owners of Tin Man told me that the mash filter was part of the original design they settled on when the brew house was coming together. Part of the reason for this choice was the novelty of the mash filter, but the major factor was that it fit into Davidson’s wish for an environmentally responsible brewery – that’s why Tin Man cans beer instead of bottling, it’s less energy consuming (maybe a 20% or greater energy savings) and better for the environment.

I did a bit of reading on mash filters before talking to Nick, and learned that they do require less water and less energy, but the point that Nick made to me that I didn’t already know was that they are more efficient in extracting sugars from the barley, so that a certain recipe will actually require less grain input than for the same beer made with a traditional lauter tun and sparging process. Less grain means that less impact on the environment (less grain grown, less watering, less herbicides, etc). Grain to be used with a mash filter can be milled to a greater degree with a hammer mill instead of a roller mill; smaller fragments (almost a flour) means more surface area and greater efficiency of wort production – this is why less grain can be used. The savings are only possible because the filter eliminates the need for the grain bed of the lauter tun.

The false bottom in a lauter tun relies on gravity to run the wort and sparge water through the husk bed. But with a mash filter, there are inflatable bladders between the filter plates that press the grain together and force the sugar water into the wort chamber. Since the barley husks aren’t required, beers with 100% adjunct grains (rice, corn, wheat, oats, etc. that don’t have husks) can be used. Tin Man hasn’t made such a beer yet, but they are thinking about it.

Beers that use 100% malted wheat or rye, or even corn, oats or rice don’t have individual husks that produce a filter bed. One hundred percent rye or wheat mashes have a tendency to be very thick and hold water; they can’t be sparged. The wort remains locked in the grain like oatmeal or even concrete. For example, Wabash Brewing makes a beer called The Unlauterable, simply because it uses so much adjunct grain that lautering and sparging becomes a true pain in the behind. The mash filter overcomes this problem, as with the 100% malted wheat beer called Walk the Lime from Tennessee Brew Works (the first North America craft brewer to use a mash filter). As another example, Latin America has a traditional corn beer called chicha de jora that has yet to be made in a commercial craft brewery. The point here is that a mash filter allows for a reworking of the mash to make previously unthinkable malt proportions and beers possible.

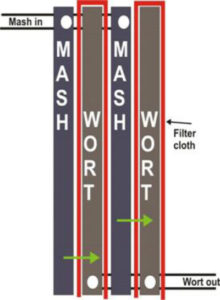

The mash filter is a series of plates (36 for Tin Man) covered in polypropylene filters that allow only particles of a certain size to pass through into the wort chambers within the filter plate assemblies (see image below). The filter plates and their attached filter sheets basically serve the same role as the barley husk bed in a lauter tun. The filter sheets in early mash filters were not so successful because they let to many polyphenols (that produce off flavors) through and produced off tastes, but the more modern filters are much more specific.

The advantages of a mash filter go beyond the environmental aspects. Nick said that it is easy to stagger mash ins and boils because the filter works so much faster than a comparable lauter tun. Multiple boils can be accomplished in a day, with less time taken for gravity filtering and for clean out. This last point is not lost on other breweries. Nick told me that when Tin Man does collaborations with other breweries, they always like to come to Tin Man for the brew. They want to see the mash filter at work, but their jaws drop when the mash out is done, the filter plates separate, and the spent grain cakes fall out on to the conveyor belt underneath that runs them to the collection bin. A quick hose out and you’re ready to go again – a system that saves, time, money and resources is a thing to behold.

Despite these factors, Tin Man is still the only brewery in Indiana using a mash filter and was only the third craft brewery in the US to opt for the system when it was purchased. This really isn’t so stunning; most mash filters are made for breweries that produce much more beer than Tin Man. Alaskan Brewing offered advice and guidance when Nick was considering this system, and they are several times the size of Tin Man. Very large breweries in the US and especially Europe are more likely to make use of mash filters, but under 150,000 barrels a year, this strategy is uncommon if not down right rare.

All this doesn’t mean that Tin Man is looking to make beers that taste like they use a mash filter. Nick explained that he wants the beer resulting from their mash filter to be indistinguishable from that made with a traditional lauter tun. Muera and some of the other companies that make mash filters like to talk about brighter worts, fewer chemicals that produce off flavors and such, but Nick corrected my thinking that these effects were discernable in the final product. The wort might be a bit cloudier than that from a lauter tun, but the cold crash and Spanish moss or other such clarifying agent takes care of that just fine. And that’s the difference between reading about brewing issues and brewing beer professionally. Things I think I know get blown away by the people who know from actual experience. Talking beer with good people is much more informative than reading about beer.

Because Tin Man has dialed in this system to produce predictable, traditional wort, Nick decided that the small batch system in the Kokomo taproom would be traditional – no mash filter there. The brewers have done the head to head comparisons and the beers coming from Kokomo are very much up to snuff; they won’t be marketed as small batch versions of the Tin Man classics. Yes, brewing is an art, but there is plenty of science and meticulous attention to detail involved as well.

So, the next time you look through a pint of Weld or Csar to admire the color, waft it past your nose to pick up the subtle aromas, and taste it because that’s the only way to get it to your stomach – take some time to think a little bit about the thought and concern for the world that has gone into that beer. A mash filter might not be part of my consideration when I choose a beer, but knowing that Tin Man is using one makes me look at their beer with a deeper respect – never mind that their beers just plain taste good. Knowledge is power; if environmental issues matter to you, then learning about Tin Man’s mash filter will make a difference to you. For me, it’s more about learning what the state’s brewers take into consideration when making beer. Indiana brewers don’t so much create beer as they are immersed in the zen of craft beer – I appreciate the opportunity to peek into that world.

Walter’s words of wisdom – There will come a time when you rejoice that the bar was full and you had to take a table. That person who just won’t stop talking about her Shih Tzu will be someone else’s problem.